The first, and for a long time the only, Legion comic I ever owned was

Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes #243. My favorite part of that issue has always been the brief appearance of the Legion of Substitute Heroes. The issue took place right in the middle of the five part "Earthwar" saga. Earth was under attack by the Khunds, but various other crises conspired to keep the Legion busy off planet. So the Subs step up to the plate to fight off the invaders. Of course, being the Subs, they were pretty quickly defeated, but by then I'd fallen in love with this plucky little band of wanna-be heroes. Well, maybe not love, exactly, but I did think that the Substitute Legion was a really cool idea. So, years later, when I spotted a copy of the

Legion of Substitute Heroes Special on the comics rack, I picked it up. I was eager to see more of these heroes who'd so intrigued me, but wasn't quite expecting what I found inside, despite the joking cover.

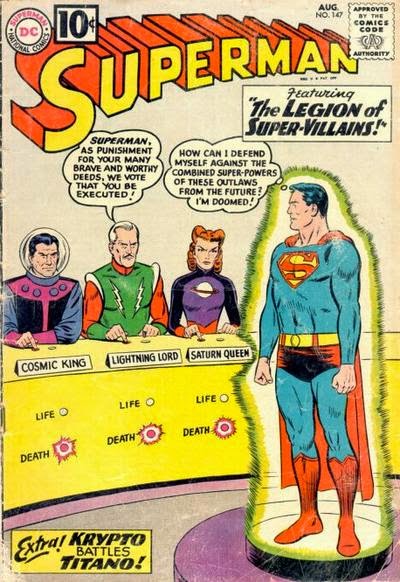

I'll talk more about that special later. Right now, it occurs to me that it might be a good idea to go over just what the heck the Legion of Substitute Heroes actually is for the benefit of any readers out there who might not be familiar with the concept. The Legion of Super-Heroes occasionally held open try-outs for Legion membership that worked kind of like the auditions for

American Idol. Would be Legionnaires would come to Metropolis from all across the galaxy to stand up in front of a panel of Legionnaire judges and demonstrate their powers in hopes of going on to Hollywood...excuse me, I meant being admitted into the Legion. In

Adventure Comics #306, five of these rejected applicants decided to form their own group. They acted as back-up to the real Legion, going into action when the proper super-heroes were unavailable. The initial membership of the Legion of Substitute Heroes consisted of Polar Boy, with the power to make things cold; Night Girl, whose super-strength worked only in the absence of sunlight; Fire Lad, who could generate flames; Chlorophyll Kid, who could speed up the growth of plants; and Stone Boy, who turned to stone.

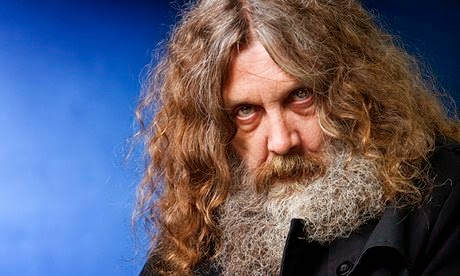

Let's face it, the Legion of Substitute Heroes is a completely ridiculous concept. Nowadays, of course, the trend is to take the silly ideas from comics written for kids and make them serious, adult, and dark. I believe that Keith Giffen would take this route with the Substitute Legion late in his run on

Legion of Super-Heroes Volume 4. However, when he first got his hands on the Subs, a decade previous, he fully embraced their inherent silliness. In fact, he not only embraced it, but enhanced, making the Subs even more ridiculous than they already were. Of course, when I think about it, I suppose that could be seen as another way of making the Subs palatable to the so-called adult comics reader.

The real significance of

DC Comics Presents #59 is reflected in the story's title, "Ambush Bug II." It occured to me as I was drafting this post in my head that perhaps someday I should write a piece on the evolution of Ambush Bug's character from his first appearance in

DCCP #52 to the first issue of his first mini-series. This post, after all, is meant to be about the Legion of Substitute Heroes. For now, it should be sufficient to say that the Bug as seen in this story is much closer to the the character we know than he was in his initial outing. There he was more of a run of the mill insane villain who actually murdered Metropolis' District Attorney on national television. In his second appearance, while still technically a villain, the Bug is not so much evil but more of a trickster. The role of the Subs in this tale is to serve as his foils.

The story is simple enough. Ambush Bug decides to bug Superman just as the Man of Steel is beginning a journey through time and the two end up in the thirtieth century. Superman has urgent business even farther into the future, so he decides to leave the Bug with the Legion of Super-Heroes for safekeeping until he gets back. Unfortunately, no one's home at Legion HQ, so he drops his prisoner off with the Substitute Heroes instead, all the while hoping he won't come to regret the decision. Needless to say he will, as the Bug quickly escapes and proceeds to raise havoc across thirtieth century Metropolis despite the efforts of the Subs and Superman to recapture him.

As with the real Legion, the membership of the Substitute Heroes underwent some changes over the years. By the time I first encountered them, the initial five Subs had been joined by Color Kid, who had the power to change the color of any object. As of

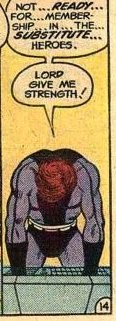

DCCP #59, Night Girl had left the team. It seems she'd only wanted to join the Legion to meet Cosmic Boy, so once she started dating him she left those losers in the Subs behind. New Subs included Infectious Lass, with the power to give people diseases, and Porcupine Pete, who was covered with quills and could project them but not with any accuracy. When Ambush Bug proves a little too much for the Subs, they call in their newly created Auxillary, consisting of Heroes who weren't quite ready to be Substitute Heroes. Those shown in this issue are Antenna Lad, who can pick up radion broadcasts, and Double Header, who has two heads. Yes, his sole "super-power" appears to be having two heads. I suppose he must have figured that his options were limited to becoming a super-hero or joining a carnival. He could have gone into politics, where a person with two faces can go far.

The Subs are portrayed in this story as well meaning but ineffective due to their limited powers and their inexperience. This is consistent with the way they were used in the Earthwar, where they totally failed to make any difference against the marauding Khunds and really only succeeded in taking up two pages of story. Being essentially an Ambush Bug story,

DCCP #59 plays up the Subs' inadequacies for comic effect. In addition to giving the Bug some more people to play off, the Subs efforts to stop him also tend to end up getting in Superman's way as he attempts to do the same. At one point, in attempt to stop Ambush Bug, Chlorophyll Kid causes a tree to spring up out of nowhere, but its Superman who ends up colliding with it.

|

| The Subs from their Who's Who entry by Giffen |

Previously in this series, I've addressed the issue of new reader friendliness, and it occurs to me that anyone not steeped in Legion history might be at first be a bit confused by this issue, as Giffen and his co-writer Paul Levitz don't take the time to introduce the Subs either as a group or individually. Even Legion fans might be at a bit of a loss, as the appearances of the Subs did tend to be few and far between. Still, I suppose, the fact that their function in the story is not really as full fledged guest stars but more as a plot complication makes such background superfluous in this case.

Giffen and Levitz do a little better on that score in the

Legion of Substitute Heroes Special, however. The book begins with a recap of the Subs origin in the form of a song, and throughout the issue Levitz provides background information on each of the members as they get their page in the spotlight.

|

| "The Ballad of the Subs" Click to Enlarge and feel free to sing along |

The story opens as the planet Bismoll, home of former Legionnaire Tenzil Kem, a.k.a. Matter Eater Lad, prepares to turn control of it planetary economy over to super-computers. Kem, now a member of the Bismollian Senate, is suspicious of the computers, but not wanting to call out the Legion on a hunch he sends for the Subs instead. We learn that Kem's fears are well founded on the title splash page when we get to see that all the giant computers resemble the Legion's old foe, the rougue computer Computo. Of course, not being up on Legion history, I actually didn't get this reference at first, only fully appreciating it after I saw Computo's entry in

Who's Who. Nonetheless, you don't have to be a Legion scholar to realize that something's amiss when the rogue computers revive another old Legion foe, Pulsar Stargrave, giving him a new robotic body, and enlist his aid in conquering and ruling Bismoll.

Meanwhile, the Subs find themselves stuck on a satellite orbiting the planet, unable to get down to the surface. After a couple of pages of this, there's a "memo" from scripter Levitz to plotter Giffen in which Levitz tells Giffen that he "can't dialogue a story that isn't going anywhere" and to "Get them the blazes down to the planet Bismoll already." Thus, without explanation, the Subs, with the exception of Infectious Lass, appear scattered at various locations around the planet.

In order to make the Subs capable of carrying their own Special, Giffen had two options. He could have made them more competent and heroic, rushing into defeat Stargrave and proving themselves at last worthy of Legion membership. Instead, he makes them even more comically inept. Things start to go wrong even before they get to Bismoll, as Infectious Lass' uncontrollable power infects Color Kid with Grandin Gender Reversal Germs, turning him into a her, and the device they use to chose a leader for the mission instead merely knocks Porcupine Pete unconscious, while Stone Boy has turned himself to stone, in which state he is totally immobile, and forgotten to change back.

Needless to say, the Subs prove fairly useless against Stargrave, succeeding mostly in getting themselves into trouble. Fire Lad sneezes and causes a major forest fire, and Color Kid finds herself trapped in a garbage incinerator. Chloropyll Kid, who previously had been depicted with a traditional trim and muscular super-heroic figure but here is shown as short and pudgy, gets himself arrested because apparently it is a crime to be fat on Bismoll.

As in

DCCP #59, its up to the more experienced former Legionnaire, in this case Matter Eater Lad, to stop the threat, though he does so with a little bit of help from Polar Boy and Stone Boy.

Their first starring role also turned out to be the Subs last hurrah, as the story ends with Polar Boy thinking "Maybe the Substitute Heroes wasn't such a good idea, after all..." He subsequently went on to disband the Subs and ultimately joined the real Legion, eventually becoming the group's leader, a post he held when the Legion itself disbanded during the Five Year Gap.

I didn't read DCCP #59 until I got

Showcase Presents Ambush Bug about five years ago. Back in 1985, I was unfamiliar with Ambush Bug and knew the Subs only from their brief cameo in

Superboy and the Legion #243, in which they were depicted as more or less traditional and serious super-heroes. So, my first reaction to the

Subs Special was something along the lines of "What the hell?" Of course, over the ensuing years, especially as I've become more familiar with Giffen's body of work, I've come to appreciate this comic for what it is. While not quite as laugh-so-hard-you'll-break-all-your-furniture hilarious as some of the early appearances of Ambush Bug, the

Subs Special is a gently amusing send up of super-heroic conventions. The story ends with a note from editor Karen Berger stating that Levitz and Giffen had gotten out of control and assuring the reader that the regular Legion title was nothing like this. The note ends "I'm sorry,everyone---really I am!"

Karen, if by some wild chance you happen to ever read this, I want to assure you that you have absolutely nothing to apologize for. In fact, let me take this opportunity to thank you, as well as Keith and Paul, for all you've done for comics over the years.